Dad and I said our goodbyes as he left for the airport early this morning. Dropped my things at concierge and had a quick breakfast before heading out.

Walked to Wawel Hill, which I’d been looking forward to visiting for months. It was already the seat of Polish monarchs for centuries before Grand Duke Jogaila married Queen Jadwiga of Poland, thus merging the two into a personal union until their confederation in 1569 at the Union of Lublin. Only a few decades later the seat was moved to Warsaw- relatively equidistant between the two historic capitals. The constituent parts of the complex are the castle and the cathedral.

The line to purchase tickets to the castle stretched well outside the door- free admission for the week in honor of Independence Day. I was scared I’d waste the entire day in line, but I had my tickets within thirty minutes.

My admission time wasn’t for a couple hours so I figured I’d visit the cathedral in the meantime. It was closed for services, of course. Wandered the complex courtyard until services let out.

Purchased a headset and then started my tour at half past noon.

A readily apparent variety of architectural styles is testament to the centuries of additions and renovations that make Wawel Cathedral an incongruent masterpiece.

It is surely a favorite of the structures I’ve visited thus far.

Pictures were strictly forbidden, but I didn’t let that stop me. I’d waited too long for this.

The cathedral is officially known as the ‘Royal Archcathedral Basilica of Saints Stanislaus and Wenceslaus on the Wawel Hill’, named in part for Saint Stanislaus whose mausoleum is the focal point upon entrance. Stanislaus was the Archbishop of Krakow in the 11th century, killed at the hands of King Boleslaw II for his vocal opposition to corruption. He served at Wawel Cathedral, as have all Archbishops of Krakow since before his time until present day.

Directly in front stands the high altar, the site of all royal baptisms, weddings, funerals, and coronations since King Wladyslaw I the Short reunified Poland in 1320 until the Partitions of Poland in the 18th century. A separate coronation took place at Vilnius Cathedral from the Union of Krewo (established personal union in 1385) until the Union of Lublin (established real union in 1569).

From the altar I was lead to Sigismund Tower. A lengthy flight of stairs took me to Sigismund Bell, the largest of five bells. It was cast in 1520 and named for King Sigismund I who commissioned it. It weighs almost 28,000 pounds and takes 12 ringers to swing it, but it only tolls on special occasions.

The view of the from atop the tower was incredible.

Walked back down to reach ‘Bards Crypt’, which contains the tombs of 19th century poets Julius Slowacki and Adam Mickiewicz, the latter considered to be the national poet of Poland.

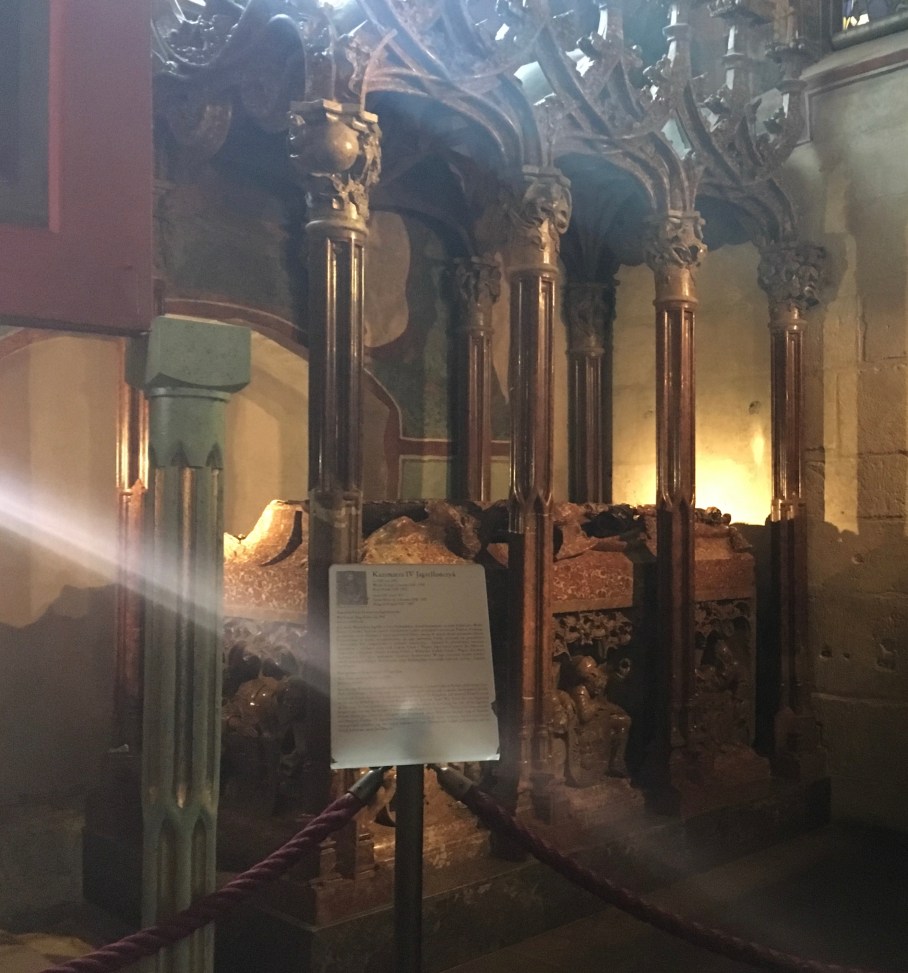

The remainder of the tour took me through the various chapels and by the royal tombs. The earliest rulers are interred in the cathedral itself, while later rulers lie in the crypt underneath. It was an unbelievable experience to stand in the presence of the kings and queens I’ve read so much about, I tried my best to inconspicuously photograph. I was particularly excited to visit the final resting place of Grand Duke Jogaila and Queen Jadwiga, whose marriage in 1386 established the basis for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Their son, King/Grand-Duke Casimir IV, rests in a chapel opposite the nave.

The entrance to the royal crypt, known as ‘Saint Leonards’, is located nearby. In addition to the later monarchs, it holds the remains of multiple national heroes including Tadeusz Kosciuszko who fought in the American Revolution before leading the efforts against partition.

I was particularly excited to see the tomb of King Stephen Bartory who founded Vilnius University.

Towards the exit stand the sarcophagi of two Polish leaders from the past century. Marshal Joseph Pilsudski was the independence leader who ruled Poland during the interbellum.

Lech Kaczynski served as President of Poland from 2005 until his 2010 death in a plane crash.

Just outside the cathedral stands a monument to her most famous of archbishops- Pope John Paul II. The only Pole to serve as Pope, Karol Jozef Wojtyla was born just outside Krakow in 1920 and served as archbishop from 1964 until his papacy began in 1978.

Wandered the castle courtyard until my tour began at 2:00.

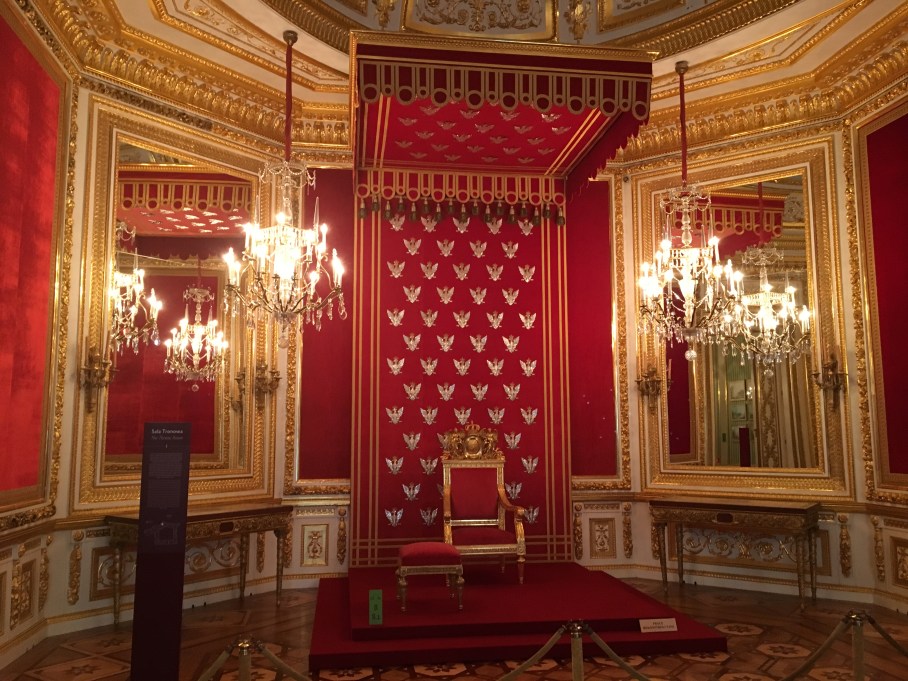

Unfortunately the only part open to visitors was the State Rooms, where Polish monarchs entertained their guests and met with the Sejm (parliament). Pictures were not allowed, but I took a discrete photograph of the primary hall where state functions were held. It was covered in tapestries from the collection of King Sigismund II Augustus that related the biblical story of Noah.

With that, I walked the old town a bit before heading to the hotel. Gathered my things and made my way to the station. Had lunch before my train left at 4:30. I managed to sleep a bit, I arrived in Warsaw at 7:00 and taxied to the airport. Blogged until my flight via propellor plane at 10:30. I arrived in Vilnius at 1:00 in the morning.